THE ALCHEMY OF LIMITATION

Why Less Gear Often Means More Sound

There’s a prevailing myth in creative technology: that more options unequivocally lead to better results. The modern digital audio workstation (DAW) presents a dizzying universe of possibility, thousands of pristine plugins, infinite tracks, and undo buttons that promise a frictionless path to perfection. Yet, many producers find themselves lost in a sea of choices, tweaking endlessly, their focus diffused.

This wasn’t a luxury afforded to the architects of some of the 20th century’s most enduring music. For them, limitation wasn’t a hindrance; it was the raw material of innovation. Their studios had a signature sound not merely because of four walls, but because of a fixed, often sparse, chain of irreplaceable gear. To know that chain intimately—its quirks, its breaking points, its sweet spots—was to master a unique sonic language.

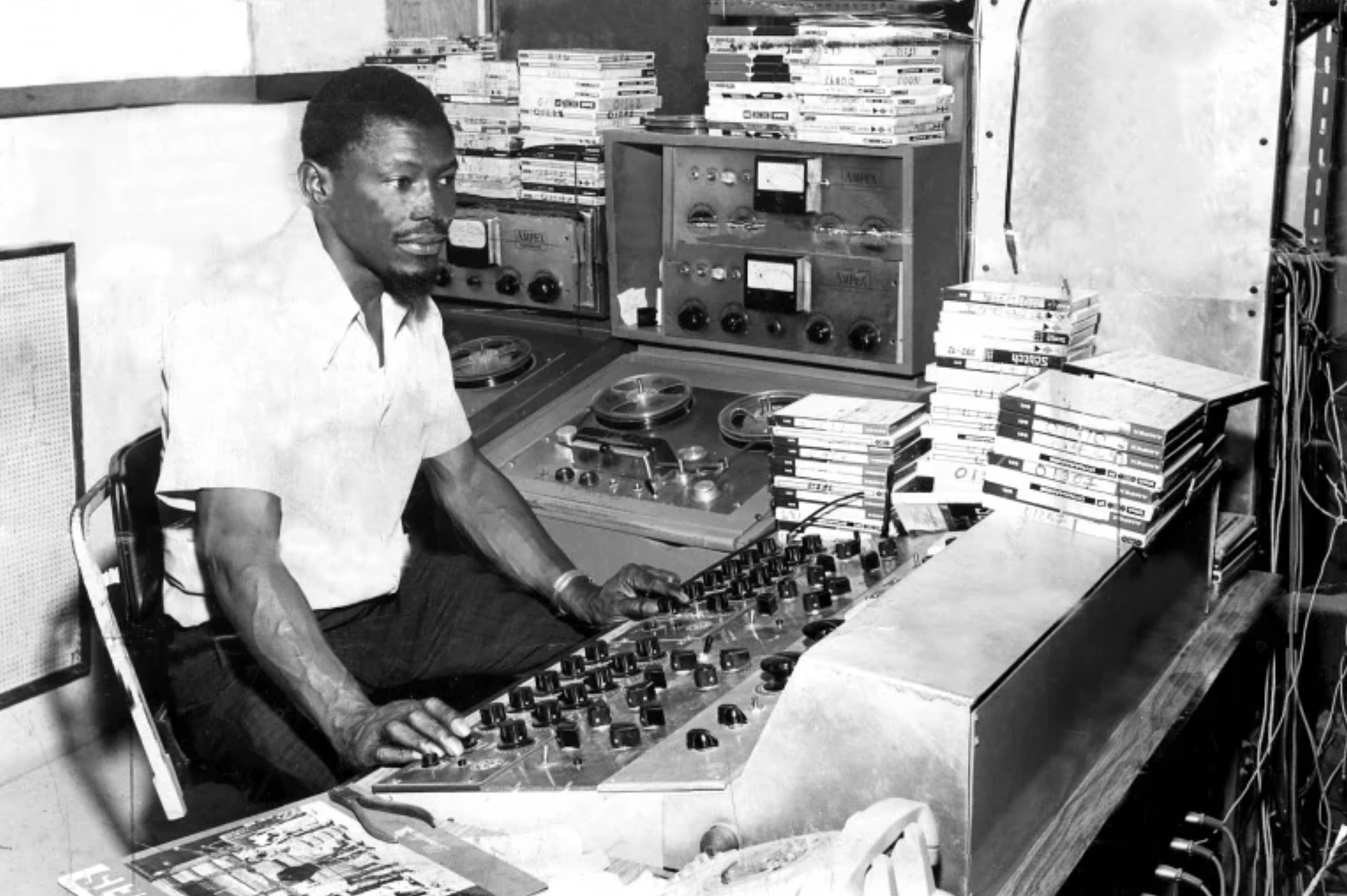

Jamaican pioneer Clement "Coxsone" Dodd

The Pressure Cooker of Brentford Road

No example is more potent than Clement "Coxsone" Dodd’s Studio One at 13 Brentford Road, Kingston. This wasn't a purpose-built temple of sound. It was a family home turned creative crucible. The technical roster was famously limited:

One primary tape machine: Often a mono or 2-track Ampex or Philips.

A custom-built, minimalist mixing console.

A handful of microphones (like the trusty Neumann U 47), often with just one or two used on an entire drum kit.

A single EMT plate reverb and a homemade echo chamber (a speaker and microphone in the studio's concrete hallway or bathroom).

In this environment, engineers like Sylvan Morris didn't have a plugin folder of 50 reverbs. They had a hallway. They couldn't sample and quantize; they had to get the perfect take. They couldn't record 48 discrete tracks; they had to balance a full band live to one or two tracks, making decisions of lifetime finality as the tape rolled.

The result? The dense, warm, and profoundly spatial sound of early reggae and rocksteady. The "one mic on the drums" technique forced a blend in the room, creating a cohesive kit sound. The limited tracks demanded that harmonies and rhythms interlock perfectly before recording. The homemade echo became the distinctive slap-back texture of the genre. The limitation defined the sound. The engineers, by pushing this limited system to its absolute limit, became virtuosos of their specific, idiosyncratic instrument: Studio One itself.

Hitsville USA, home of the Motown Sound

The Signature in the Signal Chain

This phenomenon extends far beyond Jamaica. The "Motown Sound" was born from the specific combination of a Sel-Sync 8-track machine, a Universal Audio console, and the echo chamber in the basement of Hitsville U.S.A. The gritty soul of Stax was welded to the unique overload characteristics of the McKie-designed console and the studio's "live" tracking room.

These classic studios are revered not just for their acoustics, but for their fixed signal path: a particular microphone into a particular preamp, through a particular compressor, onto a particular tape machine. This chain acted like a sonic lens, consistently coloring everything that passed through it. Artists and producers wrote and arranged for that sound. It was a known creative partner.

The Paradox of the Infinite Plugin Rack

Now, contrast this with the modern digital studio. The sheer amount of options is overwhelming: dozens of meticulously modeled compressors and EQs, endless plugins claiming "preset perfection," and an infinite palette of tools, many promising to deliver "that warm, classic sound" with plug-and-play ease. More often than not these shortcut solutions do not live up to the ads.

Furthermore, this abundance can induce a kind of creative paralysis: the "option overload." Without the forced focus of a limited palette, the search for a "sound" can become a perpetual, distracting A/B comparison. When you can change everything after the fact, the imperative to capture something definitive in the moment can weaken. The mix never has to be finished, only abandoned.

Linear Labs Studio

Finding Your Own Brentford Road

The solution to this conundrum is to consciously import that philosophy into our present workflow. An analog mindset, even if you don’t have access to the equipment.

Build Your Own "Fixed Chain": Instead of scanning 50 compressors on every vocal, choose one. Learn it inside out. Use it on drums, bass, everything. Impose a limitation. That plugin, used repeatedly, becomes your sound.

Embrace Commitments: Bounce tracks. Print effects to audio. Make decisions that stick. This mimics the finality of hitting "record" on a 2-track machine and forces you to move forward.

Cultivate Quirks: Use a single reverb plugin for an entire mix, just as they used one EMT plate. Master the imperfections.

Arrange for the Sound: Abandon the “I’ll fix it in the mix” mentality, arrangement is actually the first step of a mix. Record with intention.

The magic of Brentford Road, Motown, or Muscle Shoals wasn't in spite of their limitations. It was because of them. The limited toolbox demands deep mastery, forced ingenious workarounds, and create a unified, unmistakable sonic fingerprint. In our age of infinite choice, perhaps the most radical act of creativity is to willingly choose our own constraints, to find our signature not in having everything, but in knowing one thing profoundly.

Stay Analog-Minded,

The Linear Labs Team